For the last 8,000 years, wine’s closest companion has been food. Indeed, the two are so close that they are often thought of as inseparable. In Italy for example, when someone drinks too much, they don’t say, he drank too much. They say, he hasn’t eaten enough food yet.

But despite their closeness, wine and food (the world’s best bedfellows) differ in two very critical and surprising ways. First, in food, flavor always follows aroma. If you smell a steak, you are 100% certain you are going to taste steak flavor.

But in wine, flavor does not always follow from aroma. You might smell, say, cherries, but when you taste the wine, its flavor is reminiscent of coffee and dark chocolate. Many wine drinkers assume this schism denotes a poorly made wine. But the opposite is true. A divergence between aroma and taste is far more likely to happen with great wine which, by definition, is complex. With a great wine, a kaleidoscope of aromas and flavors reveal themselves sequentially over time, and the sensations aren’t necessarily related or predictable. (Part of the “head trip” of a bottle of great wine is that it can be completely fascinating over the course of a two-hour dinner).

The second way that wine differs from food is via the language we use to describe each. In a very practical sense, food is its own language and wine is not. For example, if I give you a strawberry and ask what does this taste like, you say a strawberry. Great. We are agreed. It is a strawberry. It tastes like a strawberry. We call that flavor strawberry, and we all know what it means. But if I give you a malbec and ask what does this taste like, and you say malbec … well, that’s not very helpful.

Because wine is not its own inherent language, most of us describe wine by resorting to comparing its flavor to objects whose meanings are generally agreed upon. We might say, for example, that a wine tastes like raspberries or like lemons. In fact, if we couldn’t use metaphors, our wine vocabulary would probably shrink to just a few words that describe the basic tastes we all share (sweet, sour, bitter, salty, savory).

Faced with the lack of a well-understood, inherent language to describe wine flavor, it’s not surprising that wine writers like me invent their own. Of course, you might find some descriptions a bit over-the-top (it’s a precocious little wine and its femininity is alluring…). But the truth is that these creative, if idiosyncratic, attempts to describe wine do carry some meaning that can orient the taster. Most people, for example, know what’s meant when a wine is described as powerful, massive, or soft. Describing a wine as being as “soft as flannel sheets” is just going one step further in the attempt to be helpful.

What I find most fascinating about creative wine descriptions, however, has to do with what linguists call semantic field theory, namely that words related to one idea all shift when one of them is used in a new way.

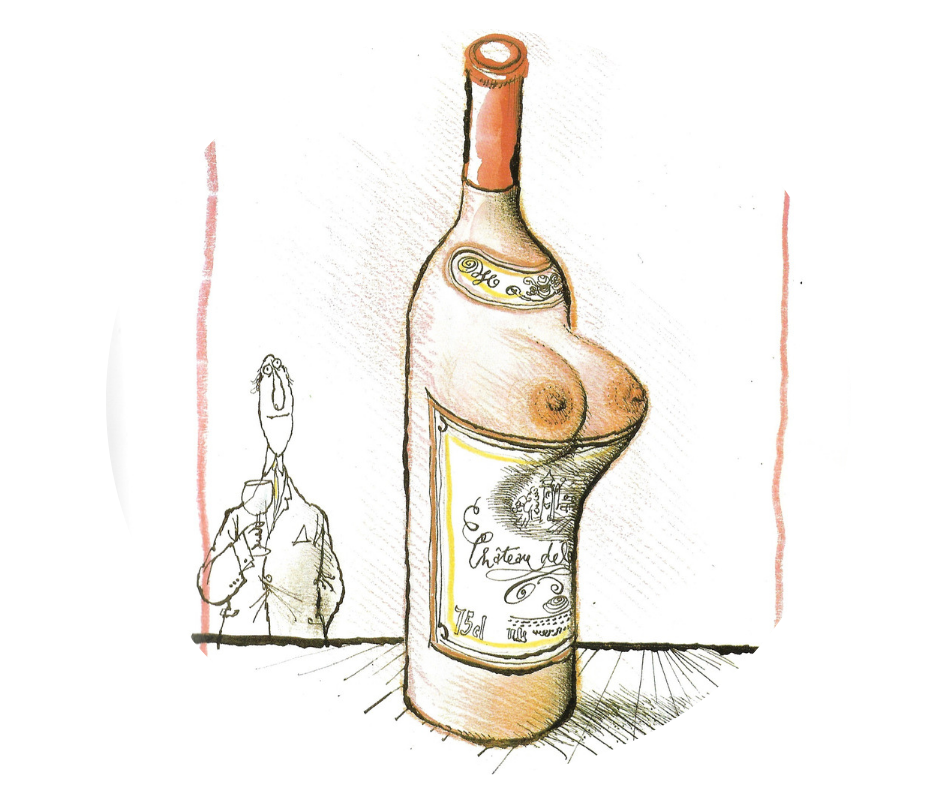

The best example of this is the use of words related to the human body to describe wine. A person can be heavy or light. The first time wine was described as heavy or light, it opened the door for all sorts of other “body descriptions” for the taste of wine. Today, for example, you see wines described as thin, fat, curvaceous, sinewy, sleek, muscular, lean, chunky, brawny, even bosomy (a favorite description for ripe chardonnay).

I give many corporate and private wine seminars, and a few years ago, one of my students was a world-famous architect. For a year, I conducted a class every month for him and a group of his friends. Wine discussions can get pretty boisterous, but over time, I realized that the architect himself never described any of the wines he tasted in class. One evening, I decided to put him on the spot and asked him to describe a Bordeaux wine we were tasting. He paused for several seconds and then said, “This wine is the cathedral at Chartes …” and went on to describe the how the flavors were lifted and graceful like the flying buttresses on the cathedral, and on and on.

I was stunned. I realized that over the whole year of classes, he had been seeing the wines. Cherries never occurred to him. Architecture was his logical source of metaphor.

In the end, it does not matter what world of metaphor we use to describe wine, but describe it we must. A green bell pepper may be a green bell pepper. But a Bordeaux can be a cathedral or a pup tent.

Illustration from The Illustrated Winespeak: Ronald Searle’s Wicked World of Winetasting by Ronald Searle